Blogs

The day after ISIS: the Middle East after Islamic State | The Western odyssey in defeating ISIS

By Kyle Orton

In this conversation on the future of the Middle East after the Islamic State (IS), we bring together experts to debate the prospects for reconstruction and governance in IS-held territory, the future of the Jihadi movement, how to mitigate against the return of IS fighters, and the future regional security framework. We ask the experts what policymakers need to start thinking and planning after the territorial defeat of the most dangerous terrorist group to date.

Within the next month, the Islamic State (IS) will likely lose its grip on its Iraqi capital, Mosul, and the operation to drive it from its Syrian capital, Raqqa, will begin. The destruction of IS’s caliphate, however, is not even close to the end of the road for the movement, not least because of the manner in which it is being accomplished.

At its core the IS movement is waging a revolutionary war, and as Craig Whiteside, a fellow with The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism has explained, this means that the focus is on legitimacy. Military victories come and go but if IS is, over the long-term, gaining acceptance — whether from support, resignation, or fear — among the population it hopes to govern (the Sunni Arabs), then it is winning. It is for this reason that IS tries to embed political victories within its military defeats.

A classic case is Fallujah. The American Marines killed many hundreds of IS jihadists to clear the city in 2004, but the battle raised the profile of the organisation, and the destruction damaged the Coalition’s cause. IS captured the city again in January 2014 and last June, when the operation against Fallujah finally arrived, IS resisted long enough to allow Iran’s proxy militias to commit sectarian atrocities, then withdrew to preserve its forces. Many in the area are now more frightened of the militias than IS.

In Mosul, at least, the US kept the militias out of the city itself. Ditto the Kurdish Peshmerga. Yet there are dangers ahead. The fact that the militias have been kept out of the fighting, while the professional forces like the Iraqi Counter-Terrorism Service (CTS) have been severely eroded, leaves open the possibility that these radically sectarian forces that answer to a foreign master might be positioned to swoop in afterwards, which would create a near-perfect political set-up for IS. Still, the CTS is a professional force that can break through IS’s defences in Mosul and there are some sprigs of optimism that a national compact can be put together in the aftermath. Neither of those things are true in Syria.

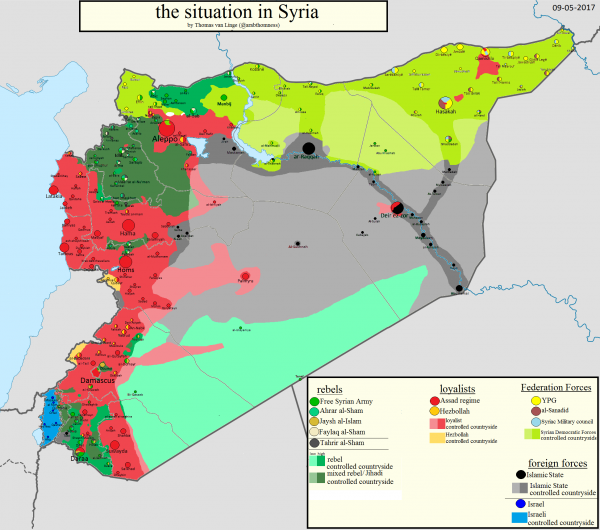

(Click the map to enlarge). Map of the situation in Syria courtesy of Thomas van Linge, @arabthomness, 9 May 2017. Twitter.

Barring an eleventh-hour reversal of policy, the US will be pushing IS out of Raqqa City using the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a force totally dominated by the People’s Protection Units (YPG), with some Arab units attached. The YPG is the name under which the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) operates in Syria. Despite the tactical proficiency and decades of experience gained from the war waged by the PKK against NATO member Turkey, as well as the unifying ideology centred on the cult of personality around its imprisoned leader, the PKK is a relatively small militia, and the casualties in Raqqa will likely be horrendous. The political fallout of sending the PKK into Raqqa is worse — even in the narrow terms of the anti-IS mission.

The problem with using the PKK-dominated SDF in Raqqa is often framed around the question of Turkey. This is a real and serious problem: the Turks have already demonstrated that they can and will disrupt an American-PKK offensive at Raqqa. The PKK seizing the city could trigger a broader war between Arabs and Kurds, and/or between the PKK and Turkey on Syrian territory, which potentially spills back into Turkey itself, multiplying the number of fissures that can be exploited by the jihadists. But Turkey is not the main problem with using the PKK in Raqqa.

All available evidence points to the local population being intensely hostile to PKK rule, opposing the PKK’s authoritarian model and being especially fearful of the PKK expelling inhabitants based on accusations of collaborating with IS. Such abuses have been recorded in other Arab-majority areas that have fallen under PKK rule in Syria, and the PKK’s use of the “pro-IS” accusation pre-emptively against specifically anti-IS political opponents from Raqqa raises worrying questions about their conduct.

Locals in Raqqa also fear that a PKK conquest would result, as it did in parts of Manbij, in the city being handed back to Bashar al-Assad and the legion of Iranian-controlled foreign Shia jihadists that keep his regime alive. If this scenario plays out it would be utterly catastrophic in human rights terms, of course, but in counter-terrorism terms the devastating effects can hardly be overstated. IS would have everything it needed to make its comeback. In the meantime, the appearance of vindication for the narrative that the West was on al-Assad’s side all along would open the way to al-Qaeda physically and politically filling the vacuum in an area from which it has been cleansed..

This use of demographically inappropriate, Shia and Kurdish forces to displace IS has been the leading vice of the Coalition campaign, ensuring that the defeat was only the resetting of the cycle and decoupling IS’s (waning) fortunes on the battlefield from its international appeal because these military defeats did not constitute political defeats.

The holding of a territory was important in building IS’s brand, an all-important asset, but it was never the basis of the movement’s legitimacy. Had the state-building project been defeated quickly by the Sunni Arabs over whom IS ruled found congenial, that could have damaged IS’s brand. Now, nearly three years on, the chance for a quick defeat is gone and the Coalition’s chosen partners allow IS to present its looming defeat as a conspiracy to fasten an alien occupation on Sunni areas. This in turn is allowing IS to mobilise international supporters against states in the West and elsewhere to “punish” them for this policy. IS’s powerful media department maintained the cause when the organisation was driven into the wilderness in 2008, and this time IS will also have an online infrastructure that can train and remote-control terrorists in the West to deliver the message that it still lives.

After it had been driven from control of urban areas into the desert last time, IS’s then leader, Hamid al-Zawi (Abu Umar al-Baghdadi), rebuked those who judged the organisation by “external appearance, or those who became tired because of length of the way and its hardship”. “The real victory begins with the firmness of [religious] methodology and patience on the path of right,” al-Zawi added. Dismissed at the time as bravado and self-consolation for his troops, in retrospect, al-Zawi looks more right than wrong. The Coalition was judging based on loss of leaders, territory, and resources; IS was judging on its growing reach among tribes and the youth in Sunni areas, enabled by IS systematically eliminating the Sunni alternatives and Baghdad increasingly proving incapable and unwilling to provide Sunnis security and services. IS was out-governing the Iraqi state, and our metrics didn’t detect that.

In May 2016, Taha Falaha (Abu Muhamad al-Adnani), IS’s official spokesman — who also approved the foreign attacks, governed Syria, and eventually served as the caliph’s deputy — gave a speech in which he made clear that the caliphate was more a cause than a destination: “Do you think … that victory is by killing one leader or another? … Or do you … consider defeat to be the loss of a city or the loss of land? Were we defeated when we lost the cities in Iraq and retreated into the desert without any city or land? And would we be defeated and you be victorious if you were to take Mosul or Sirte or Raqqa or even take all the cities and we were to return to our initial condition? Certainly not! True defeat is the loss of willpower and desire to fight.”

Falaha was soon killed by an air strike but his successor as spokesman, Abu Hassan al-Muhajir stuck to the same themes, making clear that IS views the impending losses as merely one part of a cycle, a trial through which god puts the believers to purify the herd. “Be steadfast and rejoice, for, by Allah, you will be victorious. This tribulation that you are passing through is merely an episode … which Allah grants … His slaves and thereby distinguishes the wicked from the good,” Abu Hassan said in December. To think that this is wishful thinking from IS would be a grave mistake.

The conditions in Iraq and Syria — political, social, and military — are arguably set up more favourably for IS now than in 2008. The lack of local, legitimate governance to replace IS, of a kind which could induce the population to collaborate in uprooting the underground networks that keep resources and social control in IS’s hands, has meant that IS is already showing signs of recovery in areas of Iraq it has supposedly been expelled from, and IS’s final bastion in eastern Syria has not even been cleared yet.

This blog is part of the BICOM research series The day after ISIS: the Middle East after Islamic State. You can read the other entries in the series here.

Kyle Orton is a Middle East analyst and research fellow at the Henry Jackson Society.