Blogs

Crunch time for the Kurds

By Jack May

The upcoming referendum on Iraqi Kurdish independence scheduled for Monday 25 September is likely to send shockwaves through the region. This blog by Jack May describes the likely consequences of the independence vote and argues that the Kurdish territories potentially lack the internal resilience to withstand forceful regional opposition, which may increase as the Syrian civil war and fight against ISIS draw to a close. With events moving swiftly, this paper is not an attempt to track every twist and turn of this ongoing issue, but rather seeks to assess some of the likely longer term implications.

Kurdish political ambitions are entering a decisive period. President Masoud Barzani of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), the autonomous Kurdish region in Iraq, has announced that a referendum on Kurdish independence will take place on 25 September. On the assumption it actually takes place (and despite international calls for its postponement, Barzani this week told visiting British Secretary of State for Defence Michael Fallon that the referendum will happen unless the Iraqi Kurds receive a commitment from Baghdad to begin independence negotiations, with international guarantees that agreements will be enforced) it will likely bring to a head serious underlying tensions that may undermine the relative stability and autonomy the KRG has enjoyed in recent years.

Monday’s referendum is likely to exacerbate existing tensions, potentially creating a situation in which a number of actors may be pushed into action at the risk of destabilising the region. The KRG has gambled its stability as an already autonomous region in a play for full blown independence, or at least a strengthened negotiating position vis-à-vis Baghdad. Even for supporters, it risks a military rebellion of Shi’a militias, protest from some populations not fully sold on Kurdish rule, and the outcry of neighbouring states.

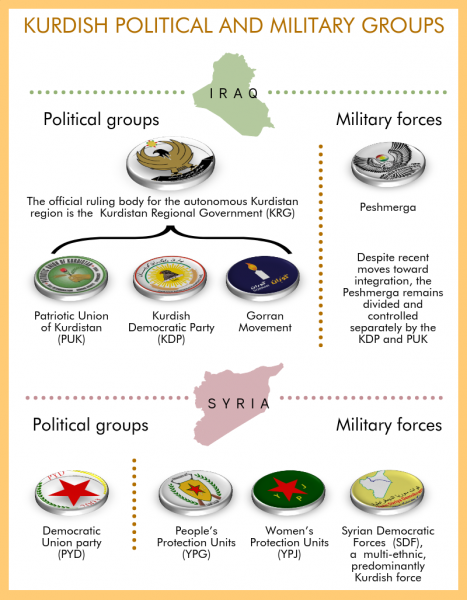

Across the border in Syria, as the fight against ISIS draws to a close, the Kurdish population, represented predominately by the Democratic Union party (PYD) and its militia the People’s Protection Units (YPG), face escalation with Turkey and an uncertain future with the US.

In both countries, the consequences of the push for Kurdish independence will revolve around several key questions: the extent of the territory the Kurds will claim; the response of regional actors; and the policy of the US.

Iraq: tensions come to a head

What territory will the KRG claim?

At present, it is unclear what territory the Kurds will claim or indeed be prepared to fight for, with areas disputed between the Kurds and Iraqi central government accounting for up to 30 per cent of the approximately 58,000 square kilometres administered by Kurds; in July 2016, KRG Prime Minister Nechirvan Barzani (Masoud’s nephew) said that these borders were “drawn in blood,” and the KRG would not withdraw from them.

However, there have been tentative signs of Kurdish efforts to establish a negotiating agenda: KRG Foreign Minister Falah Mustafa has acknowledged that land may be used as leverage in efforts to achieve recognition of Kurdish independence from Baghdad. While a “yes” vote in the disputed areas of Kirkuk, Makhmour, Sinjar and Khanaqin would not result in an immediate or automatic declaration of independence, senior Kurdish official Hoshyar Zebari has said that it would “strengthen the Kurds’ hand” in talks on independence with the central government. The week before the referendum, Nechirvan Barzani told Russia Today that Kurdistan’s future borders can only be defined through serious engagement with Baghdad, stressing that “the people of Kurdistan and the Kurds in particular do not want to impose our will on the populations and other ethnicities in this region – such as Arabs, Turkmens, Christians and all other components in various areas that are living within these borders”.

It is, however, difficult to see how the dispute over oil-rich Kirkuk, an economic lifeline for the KRG, won’t become a zero-sum game between the Iraqi government and the Kurds. With the KRG in economic turmoil and the Iraqi government seeking capital to rebuild infrastructure and reassert control it is not clear that either can afford to live without it.

Iraq, Iran and Turkey – how may regional actors respond?

Regardless of Iraqi Kurdish willingness to moderate and negotiate over territory, what remains abundantly clear is the lack of active regional state support to KRG independence. The Iraqi prime minister has labelled it illegal while an Iranian foreign ministry spokesman has reiterated Tehran’s view that “the Kurdistan region is part of the Iraqi republic” and its opposition to “unilateral decisions outside the national and legal framework”.

Turkey has developed an increasingly close partnership with the KRG in recent years, and its stance on its independence remains difficult to predict. Official comments express opposition to the referendum; Prime Minister Binali Yildirim declared Barzani’s call for a referendum irresponsible, Turkish President Racep Erdogan described it as “an error and a threat” and a presidential spokesman confirmed in August that Turkey would not recognise an independent Kurdish state.

However, the close economic and political ties between Turkey and the KRG suggest that while Turkey will certainly not assist KRG independence efforts, it may not hinder them either.

Turkey has made the KRG a major partner in the economic and energy fields. In 2013 the two signed a package of deals to build a second multi-billion dollar oil pipeline from the KRG through Turkey, with provisions for at least 10bn cubic metres of KRG gas per year to Turkey. In June 2014, Prime Minister Barzani announced a 50-year deal to export Kurdish oil to Turkey. Moreover, the volume of trade between Turkey and the KRG currently stands at around US$8.5bn. Gaining access to Kurdish oil/gas is a huge Turkish investment; Ankara may thus be unlikely to actively engage to thwart KRG independence efforts for fear of risking a key part of its energy supply. Indeed, in a visit to Baghdad and Erbil in August, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said that trade ties were unconnected to the referendum, and failed to specify any punitive measures Turkey would employ if the KRG declared its independence.

Erdogan and the AKP party also enjoy increasingly warm political ties with the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP). The relationship offers Turkey a stable partner in Iraq, a potential buffer against Iranian and Shi’a influence and potentially an interlocutor with the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK). It may also prove useful domestically, as Erdogan courts Turkish Kurd votes.

Within Iraq itself, Iran-backed Shi’a Popular Mobilisation Units (PMU), an official security body affiliated with the Iraqi armed forces, have pursued a policy of co-opting minority groups in Nineveh and Sinjar and to encourage their loyalty to both the PMU and Baghdad. Worrying reports of the PMU moving towards the borders of disputed areas, combined with bellicose rhetoric, indicate the Kurds may face violent opposition from Shi’a groups following attempts to solidify control of disputed areas.

US policy

The US has a history of strong relations with the KRG since the 2003 Iraq war, when the Peshmerga (the military forces of the KRG) played a crucial role in ousting the Ba’ath regime by supporting US efforts to occupy northern Iraq. Today, there is a US military base in Erbil, a memorandum of understanding on military coordination, and in 2016 a US agreement to pay US$22.2m in salaries to the Peshmerga. The US has found a valuable ally in the Iraqi Kurds for more than a decade and it is highly unlikely the US would just abandon the KRG, as some analysts believe may happen with the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Syria.

A US military presence in Erbil would likely deter serious escalation between Baghdad and the KRG following the referendum and the US has an interest in acting as a stabilising influence in the post-referendum confusion in order to protect its interests. However, the US is unlikely to support full-blown Kurdish independence in Iraq. The US has not endorsed the KRG’s referendum, and encourages Erbil to resolve its concerns with Baghdad constitutionally. Whilst recognising the “legitimate aspirations” of Iraqi Kurds, the State Department expressed concern that the referendum will distract from “more urgent priorities,” such as the defeat of ISIS fighters. Furthermore, a June draft of the House Defence Bill indicates congressional opposition to the referendum, stipulating that continued funding for the Peshmerga would be “contingent” upon Erbil’s “participation in the government of a unified Iraq”.

However, in the interest of protecting US strategic and economic interests in the KRG, the US may ultimately support further devolution that Barzani may accept.

Syria: the risk of escalation

What territory will the Kurds claim?

The Syrian-Kurdish question cannot be delinked from the wider context of the Syrian civil war. As such, the fate of Kurdish ambitions for territory and autonomy are at the mercy of political settlements reached as the civil war and the fight against ISIS draw to a close. The outcomes of these settlements will impact and constrain the extent to which Kurdish political ambitions can be realised.

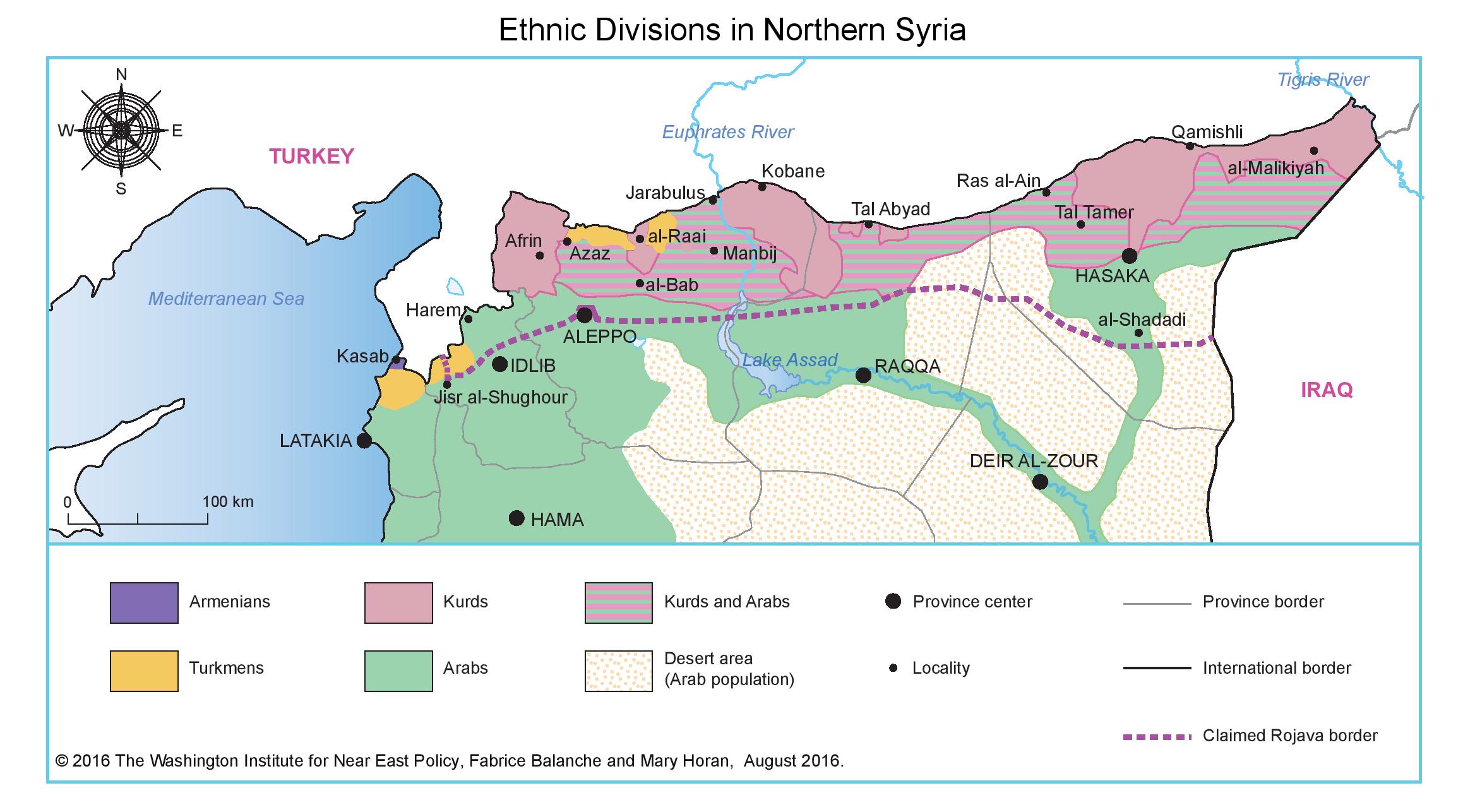

Ethnic divisions in northern Syria. Map courtesy of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

The Syrian regime, Russia, the US, Turkey and Iran will prove critical in determining the future configuration of Syria. The US and other powers have so far proved reluctant to permit the PYD/YPG to attend international fora to discuss the future status of Syria and the Kurds risk being left out and overtaken by political settlements in which they played no part negotiating.

Given the lack of territorial clarity in Syria, the Syrian Kurd territorial ambitions appear more fluid. A senior Kurd official has said that Syrian Kurds want more territory in northern Syria in return for helping the US retake Raqqa from ISIS, and laid claim to a “legal right” to a trade corridor to the Mediterranean. At present, the US has supported the SDF as the primary force in the assault on Raqqa, and is laying the groundwork for a role in its occupation post-ISIS. An official even revealed it was possible that SDF forces might eventually push west to be involved in the liberation of Deir ez–Zor and the city of Idlib, 170km west of Raqqa.

Syria, Iran and Turkey – How may regional actors respond?

Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has consistently opposed Kurdish federalism in northern Syria and will continue to do so. He has called it impossible on social and geographic grounds, and recently labelled elections held there a joke. Al-Assad also emphatically rejected a federal model for the Syrian state suggested by Russia at the Geneva Peace Talks in 2016.

If pressure to accept Kurdish autonomy – under a federal model – could not be brought to bear on the Syrian regime in times when its position was less assured, it is unlikely to change now, when the tide of the civil war has turned in its favour. Moreover, upon the final defeat of ISIS, it is unclear the degree to which the US will protect the SDF. Al-Assad has expressed a commitment to retaking every inch of Syria, and it is highly possible the SDF will be engaged as any another rebel group.

Senior Iranian politicians have also criticised the Syrian Kurds for attempting to divide Syria, and Iran will continue to support Syrian territorial integrity and al-Assad’s centralised government, which it views as the best route to achieving its strategic goal of maintaining a land bridge to enhance its influence in Syria and Lebanon.

Kurdish demands for autonomy in Syria are also likely to be heavily opposed by Turkey. Turkey has been actively engaged in stifling Kurdish efforts to establish an autonomous territory in Syria since August 2016 when it intervened in Syria to capture Jarablus from ISIS and prevent a Syrian Kurd corridor along the Turkish border from Kobane to Afrin.

The PYD has been unable to convince Ankara it isn’t an offshoot of the PKK – a Turkish-Kurdish party considered by Ankara and the West to be a terrorist organisation – and that it does not represent a launching pad for PKK attacks on Turkey. For Turkey, the domestic Kurdish threat is inseparably linked with the perceived threat from northern Syria. Assurances from the PYD co-leader that US arms flowing to the YPG will not end up in PKK hands haven’t softened Turkish military action in Syria. On 4 June the YPG reported the death of 111 of its fighters during offensives by the Turkish Army and Turkey-backed Syrian rebel groups in northern Syria.

Turkey has consistently criticised the US tactical alliance with the SDF (even threatening in May to strike US forces partnered with Kurds), and has aggressively fought to prevent the SDF from liberating Raqqa. According to the Turkish envoy to the US, Ankara offered ‘‘tens of thousands of troops’’ for the Raqqa campaign, proposing that a Turkish-backed Syrian rebel force include Arab elements of the SDF and even a desire for US troops to form the bulk of the force. In June the Turkish foreign minister called for a “joint mechanism” with Washington to ensure that Turkey is present in the retrieval of heavy weapons lent to the YPG once Raqqa is liberated, a promise made by the US that has not reassured Turkish officials at all.

Recent developments indicate a substantial ramping up of tension between Turkey and the PYD. In June Turkey and Syrian Kurdish groups exchanged fire between Turkish artillery and YPG targets near Azaz. This was followed by a statement by YPG Commander Sipan Hemo expressing a commitment to “liberate” the area between Azaz and Jarablus held by Turkey-backed Syrian rebels. As the SDF-led assault on Raqqa rages, Turkey has mobilised thousands of troops to combat the YPG in Afrin; there is speculation that Turkey is seeking a Russian green light for an operation to take Afrin in return for securing a Russian de-escalation zone at Idlib. Kurdish YPG commanders have responded that the Turkish mobilisation has reached the “level of a declaration of war”.

US Policy

The increased US-Kurd collaboration of recent years has been called a “new stage in their strategic and special relationship” by Kurdish media outlet Rudaw. It is, however, likely to represent the peak of this relationship with “strategic and special” more accurately substituted for “temporary, transactional and tactical,” to borrow the words of a senior State Department official. All actions by the US suggest a prioritising of the destruction of ISIS and recognition of the Kurdish-dominated SDF as the best tool to achieve this.

The Syrian Kurds have set much in store for endorsement of Kurdish autonomy. The US has repeatedly reiterated acknowledgements of the “legitimate aspirations” of the Kurds and defied Turkish demands to cease working with the SDF. In recent months, the US has extended its military deliveries to the Syrian Kurds in the build up to the assault on Raqqa.

A US military presence in Kurdish areas in Syria has so far proved useful as Turkey has avoided attacking areas with US bases. The Astana process has however reinforced the emerging picture of US marginalisation in Syria. There have been signs of strains in the US-Turkey relationship, with Turkey publishing the locations of ten US military bases in mid-July, emerging reports of Ankara and Moscow’s deepening relationship as guarantors of the deconfliction zones, and a visit by the Iranian chief of staff to Ankara. The background to the Turkish mobilisation near Kurdish controlled Afrin may indicate that Turkey is looking for Russian cover in attacking the Kurds in northern Syria. If escalation resulted in full-scale war, US options – short of putting more boots on the ground – would be limited. At a private roundtable at the Herzliya conference in Israel in June, a PUK official stated that “if tomorrow US doesn’t support Rojava, it can’t survive”.

US room to manoeuvre on the Syrian Kurdish question will likely be determined by how the Kurds position themselves as a regional stabiliser or destabiliser, and as a help to US policy objectives in the region. As the primary components of the on-the-ground anti-ISIS coalition, the SDF and the KRG have proven reliable partners in constituting the military thrust of US efforts to reach a post-ISIS stabilisation of the Middle East.

It will be essential for the Kurds to retain their usefulness to the US. In the short term this will include playing a constructive role in filling the vacuum left by ISIS in Raqqa. Concern has been expressed over their ability to manage the predominately Arab population. However, some commentators have suggested a compromise: shared governance between a Syrian regime and PYD-led local government structure acting through co-opted local Arab elites. The Kurds are already working with the Syrian Elite Forces (SEF), a unit comprising of Arab Tribesmen from around Raqqa – seen as “critical to restoring security and governance,” according to spokesperson for the US-led global coalition to defeat ISIS, Col. Ryan Dillon – to communicate with local tribes. A post-liberation committee to govern Raqqa has already been set up, and has a Kurdish minority. The Kurds can continue to be useful to the US by evolving this process and working toward stability east of the Euphrates.

In the longer term, Kurdish forces might prove an invaluable US ally on the ground to balance increasing Iranian influence, especially in light of reports that Iraqi PMU, supported by Iran and Syrian regime forces, are taking over areas of the Iraqi-Syrian border following ISIS’s ousting, and Iran is attempting to create a route to the Mediterranean.

However, the Kurds may also become a source of regional instability that distracts from US efforts to broker Sunni Arab unity. Much will depend on what the Kurds do next – the territory they claim, the diverse populations they try to govern, the extent to which they allow Sunnis to return to territories post-ISIS, and the degree of factional infighting and opposition to the strengthening of the old state system.

The internal challenges of statehood

Putting aside the lack of regional and international support for Kurdish independence, questions also remain regarding the viability of the Kurdish states-in-waiting.

In Iraq, the Kurds face the challenge of rebuilding their weak economy. The KRG is in the throes of a severe economic crisis as a result of a slump in oil prices and the high military expenditure of recent years. The US has stepped in to pay Peshmerga salaries and civil servants have sometimes gone weeks without payment. While efforts to diversify income through natural gas exports continue, the crisis has hit hard.

Both Rojava (the Democratic Federation of Northern Syria) and the KRG must also contend with an array of additional challenges: the KRG contains 2m refugees and internally dispersed persons; Arabs, Turkmen and Shi’a populations who oppose Kurdish rule have been encouraged by Shi’a militias (In Iraq) and Syrian regime forces (in Syria) to oppose the Kurds; the borders of a Kurdish entity remain uncertain even amongst the Kurds themselves; and Kurdish political groups have been prone to terse domestic disagreements and territorial disputes and tensions continue to exist between the PUK and KDP aligned elements of the Peshmerga, and the respective territory they each protect.

Many of these internal challenges are not exclusive to the Kurdish areas. Baghdad and Damascus face the same sectarian, economic and humanitarian challenges, porous borders and weakened infrastructure. However, Iraq – and to a certain extent Syria – enjoy international support for their territorial integrity.

Conclusion

Kurdish ambitions in Iraq and Syria are entering a new and uncertain stage. The referendum in Iraq will stir the pot of sectarian tensions in disputed territories, alarming Baghdad and neighbouring states. Whatever the result of the vote, tensions are likely to increase even before the referendum, as various groups take advantage of the uncertainty to establish a stronger position in certain areas prior to an outcome.

In Syria, the Kurds potentially face escalation with the Syrian regime, Turkey and Iran as the territorial fight against ISIS reaches the endgame. If this escalation continues, the US-YPG relationship will be tested in a post-ISIS strategic environment where the US may revaluate how far their commitment to the Kurds stretches.

With the referendum bringing tensions to a head in Iraq, and Turkey pressing the issue in northern Syria, it is difficult to see the Kurdish areas as possessing the internal resilience to weather the onslaught of any forceful regional opposition to Kurdish independence that may emerge.

Jack May works at the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) and is a former Research and Communications intern at BICOM. The views represented in this blog are the author’s own and do not necessarily represent the views of BICOM.