News

Judicial Reform

Israel’s new coalition government is committed to a programme of wide-ranging judicial reform designed to limit the power and independence of the Israeli judiciary. The speed and intensity with which the process has begun has proven hugely contentious and divisive, with Israel riven by dispute and fracture regarding the issue.However, although the current crisis is unprecedented, it can be understood as the culmination of long-held Israeli differences on the proper role of the judiciary.

Arguments over Judicial Reform

Both reformers and their opponents assert that theirs is a campaign for the salvation of Israeli democracy.

Reformers have long argued that a democratic deficit is produced by an unelected judiciary capable of overruling the decisions of democratically elected politicians. They claim that since the so-called “judicial revolution” of the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Aharon Barak in the early 1990s it has been engaged in “activist” overreach. Examples given often include: judgements made in 2012 and 2017 ruling that compromises reached with ultra-Orthodox parties over the question of ultra-Orthodox service in the IDF breached principles of equality; decisions from 2013, 2014, and 2015 overruling government legislation concerning the detention and eventual resettlement of illegal migrants and asylum seekers; a 2020 ruling against the retrospective legalisation of illegal West Bank settlements on the grounds that such would constitute harm to Palestinian property, equality and dignity.

Although the Supreme Court has overruled only 20 laws out of around 1300, the nature of some of the issues concerned in such rulings led to an anti-court convergence of interests among the ultra-Orthodox, settlers, and other right-wingers. This is despite the fact that court has, on occasion, intervened in a fashion more likely to please the right-wing than the left; as, for example, in 2005 when it ruled in favour of increasing compensation for settlers evacuated following the disengagement from Gaza and some areas of the West Bank. Reformers also allege that the low figure of Supreme Court interventions is deceptive, and that the self-perpetuating domination of left-wing opinion from both judges and government legal advisors has prevented right-wing governments from even floating desired legislation, so sure are they that it would be prevented by the legal establishment.

Another complaint has been that the Israeli judiciary, and the legal establishment more broadly, functions as a self-elected and self-perpetuating “club”, whose membership is largely restricted to a liberal, Ashkenazi “elite”, and that wider participation is urgently needed to reflect the diversity of Israelis and Israeli opinion.

Opponents of the government’s proposed reforms, some of whom agree with the need for judicial reform in principle or in moderated form, argue that Israel’s democratic culture is unique. Israel possesses no second chamber, nor a written constitution, and the list system (which concentrates power over MKs to party leaders, as opposed to their being parliamentarians answerable to their constituency) ensures that the executive is generally able to exercise de facto control over a majority of the Knesset.

In this context, reform critics claim that the existing system provides for a vital separation of powers and that an independent judiciary, with partial capacity for overruling the legislature and executive, provides a crucial brake on executive power and functions as an essential guarantor of liberal democratic norms and minority rights. The system proposed by the reformers, they fear, provides for the tyranny of the majority, and a blank cheque to this and future governments, of whatever political orientation.

Critics also note that the high esteem in which Israel’s independent judiciary is held internationally functions as a protection on Israelis from subjection to the authority of international courts, and that weakening the judiciary would also weaken this protection.

The Government’s Moves

In early January 2023, Justice Minister Yariv Levin – a Likud MK and long-time proponent of judicial reform – announced the government’s reform agenda. The Knesset’s Constitution, Law and Justice Committee, chaired by Religious Zionism MK Simcha Rothman, then proceeded to deliberate on and refine the details of Levin’s broad proposals. It now plans to roll out a multi-stage judicial revolution. The first elements have progressed sufficiently to hold a first committee vote concerning the makeup of the committee to appoint judges and the Supreme Court’s ability to strike down “Basic Laws” (laws holding quasi-constitutional status).

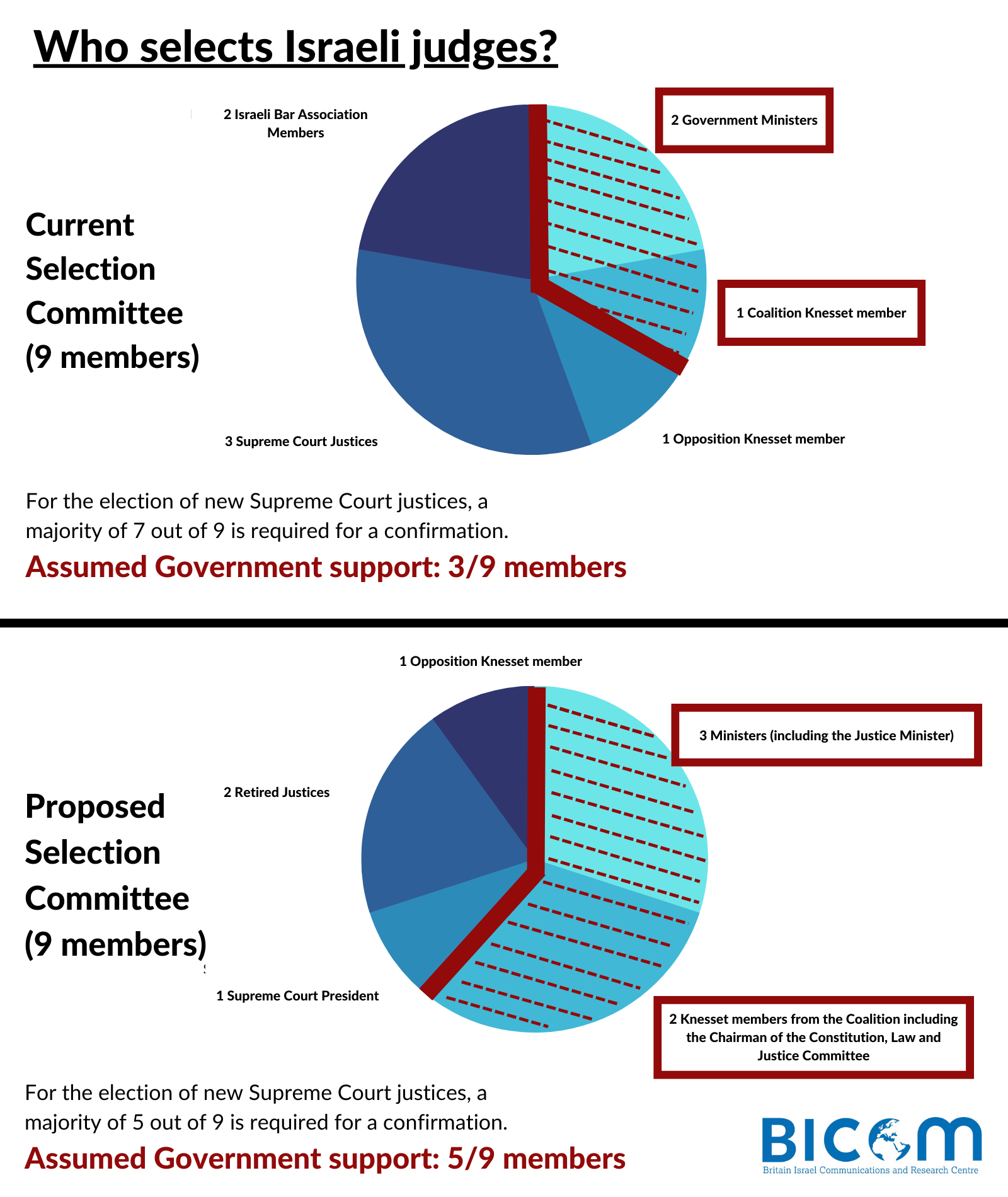

The reformers are pursuing greater political power on the Judicial Selection Committee, which appoints judges at all levels of the Israeli judicial system. At present the committee is composed of nine members: two government ministers; two other Knesset members; three Supreme Court justices; and two representatives of the Israel Bar Association. For the election of new Supreme Court justices, a majority of seven is required for a confirmation.

Under the proposed new version, the Judges Selection Committee will remain comprised of nine members, but its makeup altered to: the Supreme Court President; two retired justices appointed by the Justice Minister with the approval of the Supreme Court President; the Justice Minister; two other ministers to be determined by the government; the chairman of the Constitution, Law and Justice Committee; one MK from the governing coalition; and one MK from the opposition. Additionally, the majority needed to approve the appointment of a Supreme Court judge will be reduced from seven to five. On February 8th 2023, opposition members succeeded in “running out the clock” on the committee, delaying a first vote on the Judicial Selection Committee and Basic Law reforms until the next week, allowing time for the organising of a mass protest the following Monday.

The next phase in the Constitution, Law and Justice Committee’s reform schedule will involve composing legislation stating that for the Supreme Court to disqualify non-Basic Laws, all fifteen justices must hear the appeal and vote unanimously in favour. After that, the next reform is set to concern the establishment of a Knesset override of Supreme Court decisions. At present, no such parliamentary override exists, and while moderate reformers have long suggested that a safe override could be implemented requiring, for example, two thirds of MKs or a certain percentage of opposition MKs to vote in favour, at this point the government is pursuing an override by a “simple majority” of 61 MKs.

Later reforms will include an alteration of the independent status of legal advisors to government ministers. At present, ministers are bound by the legal interpretation of their legal advisors. The new law would allow ministers to appoint their own legal counsel with a limited advisory role. The abolition of the Supreme Court’s ability to overrule administrative decisions of the government on the grounds of “(un)reasonableness” will also be pursued. (The court cannot strike down Knesset legislation on these grounds.)

The government and Supreme Court clashed on the reasonableness question early after Levin’s announcements, with justices voting 10-1 to bar Shas leader Aryeh Deri from being appointed Finance Minister. The judges’ decision was based partly on the reasonableness principle, and partly on their conclusion that Deri had lied to the Israeli magistrate’s court when accepting a plea deal for a 2021 financial conviction which included the guarantee that he would retire from public life. The verdict required that Netanyahu fire Deri, though coalition figures pledged his return and argued that the appointment of cabinet members is a perfect example of court overreach of on matters that should be the sole purview of the government. Deri’s return could conceivably be facilitated by removal of the grounds of reasonability, but the barring of striking down Basic Laws could, if applied retrospectively, also be used. In late December 2022, Basic Law: The Government was modified to allow for a convicted felon to serve as a minister as long as their offence had not been punished with a custodial sentence.

Backlash to the Reforms

Opposition to the proposed reforms has been intensive since Levin’s announcement. Regular protests have been held on Saturday evenings throughout January and early February, while a number of high-profile Israelis have made public interventions. And, while pushback from Supreme Court chief justice Esther Hayut and from the political opposition was to be expected, the variety of sectors of Israeli society from which reform critics have been drawn has also been striking.

Bank of Israel Governor Prof. Amir Yaron warned Netanyahu in late January of the likely negative economic impact of the reforms, citing a probable decline in foreign investment and damage to Israel’s international credit rating. His warnings came days after two of his predecessors, Karnit Flug and Jacob Frenkel, had made similar predictions. Israel’s hi-tech sector – responsible for some 15% of GDP – has also baulked, en masse, and become an influential element in the protest movement. Nine prominent hi-tech firms, including WIZ, Papaya Global, Verbit, Disruptive, and Skai have announced withdrawal of operations and funds worth billions of US dollars from Israel. Hi-tech workers have already joined protest walkouts, while over 200 companies are expected to follow venture capital firm TLV Partners’ lead in allowing employees to strike next Monday.

Medical professionals have also joined strikes; during one walkout in late January, Sheba Hospital was the only Israeli hospital operating at full capacity. Meanwhile, protests by IDF reservists have been joined by a number of formerly high-ranking officers, including former Mossad head Tamir Pardo, former IDF Deputy Chief of Staff Matan Vilnai and Maj. Gen. (res.) Tal Russo. Moshe Yaalon, Ehud Barak, and Yair Golan – all former generals as well as political figures – have been at the forefront of opposition to the reforms. In a column published by Yediot Ahronot, Barak called on Israelis to engage in unprecedented levels of protest in the coming days, even suggesting that opposition MKs commit to a hunger-strike. Dozens of former Directors General of government ministries, as well as significant numbers of civil society organisations have also been vocal in opposition. Israel’s closest international allies, too, have signalled their concern.

The Process Moving Forward

The initial vote of the Constitution, Law and Justice Committee on the two concrete elements of the reforms will occur next week to be followed, if affirmed, by a Knesset plenum vote on a first reading. The government’s majority in both the committee and the plenum means that an affirmative vote is certain in both cases; the best the opposition can do is to use procedural motions to delay, though they might decide that boycotting the vote is a more powerful means of symbolising their disdain.

While the usual Saturday protest will continue – including, in an unprecedented development, in the Etzion bloc settlement of Efrat – larger demonstrations are likely to be seen on Monday, outside the Knesset. Large-scale strikes are expected, though Israel’s largest labour union, the Histadrut, has so far not committed itself. Its reasoning is that judicial reform is not a labour issue, while it also remains locked in delicate negotiations with the government over a public sector pay-rise.

President Isaac Herzog has sought to pursue a mediating function, warning of the possibly irreparable damage to the unity of Israeli society if the divide over judicial reform continues. He has suggested forming a cross-parliamentary committee to consider alternative reforms more representative of an Israeli consensus, though his efforts have so far proved unsuccessful. Hayut has made similar suggestions, with the crucial caveat that any changes only become effective from the next Knesset.

Some retain hope that Netanyahu – in the past a vocal supporter of an independent judiciary – will opt to moderate the reforms after the first Knesset reading. He is, however, under pressure from within the coalition to stand firm. Senior United Torah Judaism party figures have been quoted as threatening to withdraw from the government if Netanyahu either backs down or else agrees to concessions which significantly alter the content of the reforms. While such a threat should be treated with scepticism, it is reflective of the strength of feeling from within the other factions in the coalition. Meanwhile, Attorney General Gali Baharav-Miara, another critic of the proposed reforms, has argued, by letter to the Prime Minister, that his involvement with judicial reform is a conflict of interests given his ongoing personal legal case.

Levin has stated that these reforms are only the first stage. Speculation abounds that future reforms could include removing automatic seniority of the President of the Supreme Court, lowering the retirement age of judges, and the splitting the role of the Attorney General.